Reentry

/We’re often asked which transition is harder, America to Zambia or Zambia to America. Truth be told, coming home from Zambia is harder because the jet lag is rougher for us moving west to east, and the noise and busyness of the U.S. feels a bit overwhelming after the relative quiet here. That doesn’t mean, of course, that it isn’t difficult to transition to Zambia. It is, although it’s far easier now than when we first began especially because of our deep friendship with Percy Muleba and his family, and our comfort level here. Percy says we’re 60% Zambian now!

Still, the contrast between our cultures requires a bit of adjustment, especially seeing the daily struggles our friends face in Zambia and Namibia. The drought has been very bad this year, and the maize crop has been lost because of the limited irrigation available. The heat has been intense, as well. When we arrived in Livingstone, daily load sheddings (blackouts) were in place with no published schedule, making it very hard for families and businesses without generators to plan and live. The exchange rate has skyrocketed so that the dollar is now worth twenty-five Zambian kwacha and nineteen Namibian dollars, inflation is high, and unemployment is raging. We just found out, for example, that the unemployment rate in Namibia is 47%! Yes, you read that right. We recently heard that one of our favorite former students, Beverly Inonge, has still not received a teaching position. She’s been waiting almost ten years if our math is correct. She’s married now and doing well, sharing the gospel daily through her small business, but…

In the midst of this, over and over again we find pastors and leaders who are very, very eager to the point of desperation to be trained. The desire for learning is intense, making it a joy to teach and a pleasure to build relationships with these men and women.

This year, we began by transitioning to a brand new Namibian community called Divundu where we began Phase 1 with a new group of pastors and leaders, eighteen men and women from several small churches. Thankfully, it went really well. The students were wide open from day one which was a bit unusual, small group breakouts were very productive, and great questions were raised about on the ground realities in their churches and community. We also enjoyed very meaningful conversations over dinner with two pastors and their wives, and our accommodations were lovely. We even had a couple of hours to take a short game drive one afternoon which was wonderful. And, the intense heat broke, dropping temperatures from the high 90’s to the mid to upper 80’s. Ahh…

This coming week, we are very excited because we have a social hour planned with the teachers at the Khwe community school in Chetto on Monday. We’ll return on Wednesday to sit in on some of their classes and then follow up with them on Friday. Our goal is to build relationships with these fourteen teachers, two of them Khwe, as we continue to pursue the Lord’s leading in how we might encourage these teachers who are on the front line, and possibly make a difference in this desperate community. The unfolding of God’s plan for us in the Khwe community has been slow, but we are definitely moving forward. Please pray for us!

Today, we worshiped at our friends’ church and Doug preached on discipleship from the first chapter of John. Pastor Jack and Kalenny have warmly welcomed us through the years and we so enjoyed being with them. It’s always a joyful privilege!

As always, we are deeply grateful for you, for your partnership in our mission and your prayer support. Without you, we would not be here. We remember you in our prayers. Thank you! And remember, where we go you go!

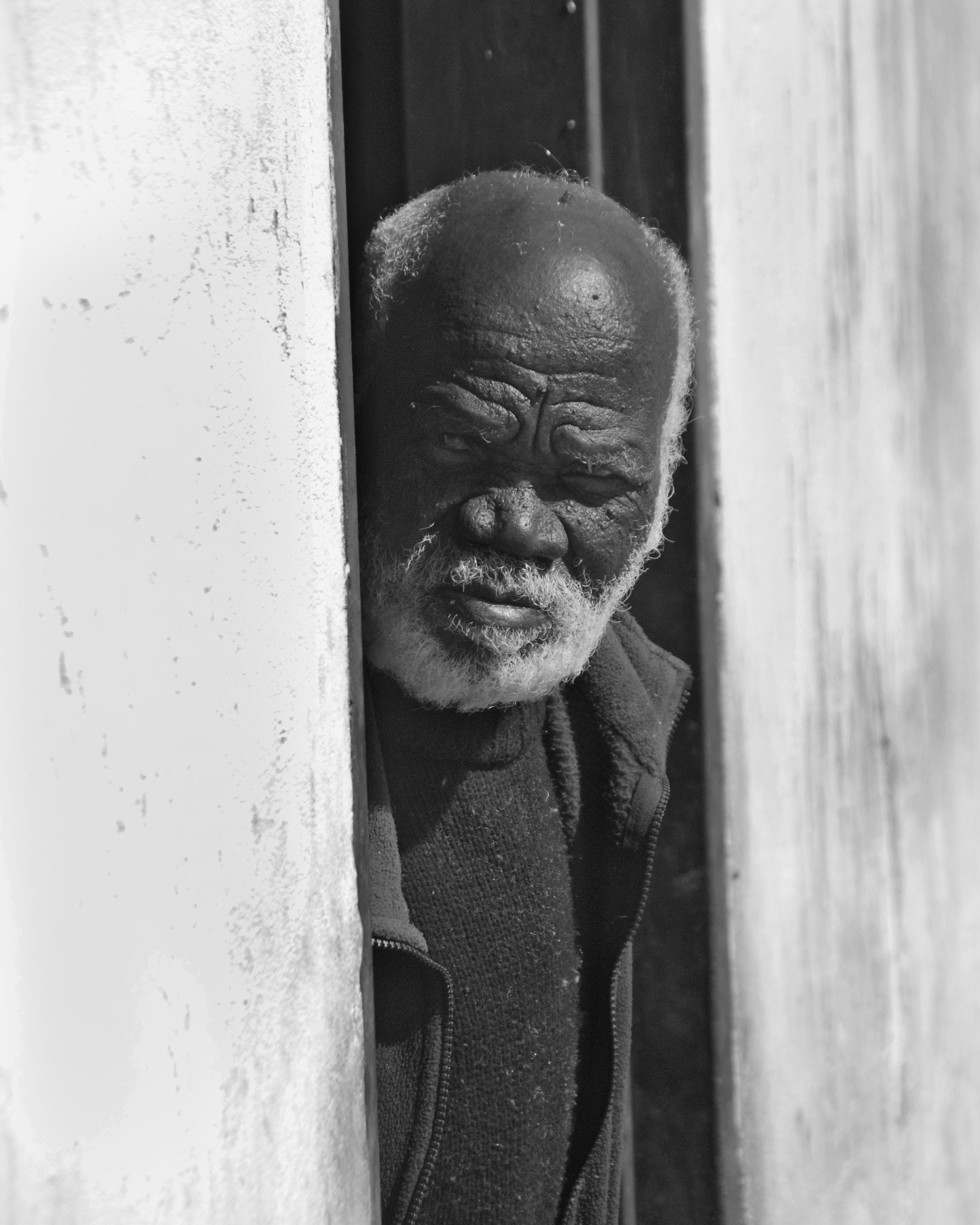

Divundu Phase 1 (L to R): Blasius, Wensel, Joseph, Albert, Hendrina, Cornelius, Joseph (kneeling), Adonia, Patricia, Marthin, Augusta, Peter (kneeling), Angeline, Annety, Markus and Pastor Jack

The Divundu students really engaged during their small group breakouts!

We were pleased to have five women and twelve men in our class.

Pastor Jack and Kalenny discipled now Pastor Markus and his wife, Belinda, for three years in Katima Mulilo. Markus and his wife are now planting a new church in Divundu. He was an excellent convener!

What a sunrise view from our lodge room!